Free Consent- Coercion

In the previous article, the causes of consent not being free were introduced. In this article, one of those causes, coercion, would be dealt with in detail.

Definition

Coercion literally translates to the use of force to make a person do something which he does not intend to do or make him/her abstain from doing something which he intends to do.

Coercion is

defined under section 15 of the Indian Contract Act,1872 as

“ ‘Coercion’

is the committing, or threatening to commit, any act forbidden by the Indian

Penal Code (XLV of 1860), or the unlawful detaining, or threatening to detain,

any property, to the prejudice of any person whatever, with the intention of

causing any person to enter into an agreement.

Explanation.

— It is immaterial whether the Indian Penal Code (XLV of 1860), is or is not in

force in the place where the coercion is employed.”

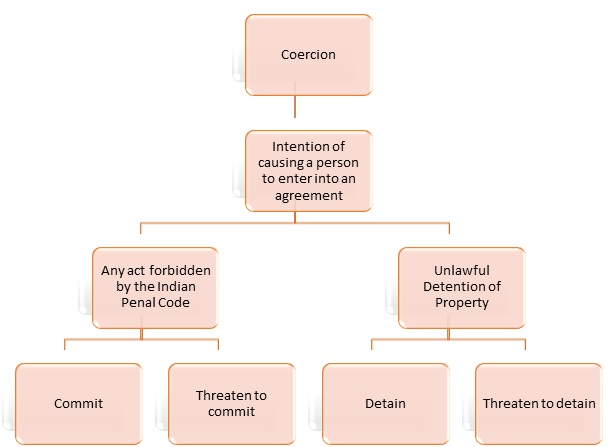

The elements of coercion can be explained through the following chart:-

The first element i.e. intention is the most important for any act to be construed as coercion. A person should be committing or threatening to commit the acts specified in the section with the intention to cause another person to enter into an agreement to create an impression of coercion. There are two specific actions mentioned in the definition which would constitute as coercion. They are: -

1.

Any act forbidden by

the Indian Penal Code-

Section 15 states that if a person does any act which is forbidden by the

Indian Penal Code or threatens to do so, in order to cause another person to enter

an agreement, he commits coercion. It is not necessary that such coercion

proceed from a party to the contract or is directed immediately against a

person who is intended to enter into a contract.

For example,

Penny threatens Sheldon to kill him if he does not transfer his property to

Leonard. Thus, Penny threatens to commit murder which is a crime under section

300 of the Indian Penal Code.

Another example

would be, Kaleen Bhaiyya, a local goon threatens Guddu to kidnap and rape his

minor sister, Dimpy if he does not agree to get her married to Kaleen’s son

Munna. Here Kaleen bhaiyya threatens to commit kidnapping and rape which are

punishable offences under the Indian Penal Code to get Guddu to give consent

for marriage on behalf of Dimpy as her guardian.

It is required

by the phrase “act forbidden by the Indian Penal Code” for the court to

adjudge in a civil suit whether the contended act of coercion is such to amount

as an offence. In a case of Chikkam Amiraju v. Chikkam Seshamma, an

issue arose that whether a property release executed by a wife and son as a

result of a threat of suicide by the husband is to be understood as an effect

of coercion or not? It was held by the court by a majority that the threat of

suicide amounts to coercion and thus the release deed is voidable. The issue

arose on the difference of opinion of whether suicide is an offence under the

IPC or not? The majority opined that suicide is an offence. It is not

punishable because once it is committed there is no one left to punish but that

does not mean that it is not forbidden. The definition of coercion specified

that it includes acts forbidden by the IPC. Therefore, a threat to

suicide will amount to coercion according to the definition laid down in

Section 15. Judge Oldfield dissented on the ground that unless an act is not

punishable it is not forbidden.

A meagre threat

of bringing criminal charges against someone does not amount to coercion as it

is not by itself forbidden by the IPC. However, threatening to bring a false

charge is coercion (Askari Mirza v. Bibi Jai Kishori). For example, Kashish

threatens her boss to bring a fake sexual harassment case against him if he

does not give her a promotion. This will amount to coercion and the promotion

will thus be voidable.

2.

Unlawful detention of

property

An illustration

of unlawful detention as coercion can be seen in an early case, Astley v.

Reynolds. In this case the plaintiff plighted a plate to the defendant for

£20. After three years, when the plaintiff came to redeem his plate, the

defendant refused and demanded an interest of £10. The plaintiff was in urgent

need of the plate and thus paid the interest to redeem it. He then filed a case

in court for recovery of the extra amount paid. The court allowed the action

for recovery. It was held that the plaintiff was in immediate need to his plate

and the defendant extracted an extra amount of money from him by refusing to

return it.

Another example

is when Fizer, a multinational company, fires an employee named Rajesh. Rajesh

gets hold of some confidential information and he threatens to release it to

the public if the company doesn’t hire him back. The company hires him back.

Such appointment is voidable later on at the option of the company because it

was made due to coercion. (Muthiah Chetti v. Karuppan Chettiar)

Effect of

coercion on the agreement

If consent to an

agreement is given due to coercion, it does not make the agreement void ab

initio (void since the very beginning) but it makes the agreement voidable at

the option of the party whose consent is not free. This rule is provided under section

19 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. The relevant portion of the section is

as follows,

“When consent

to an agreement is caused by coercion, fraud or misrepresentation, the

agreement is a contract voidable at the option of the party whose consent was

so caused.”

Therefore, the

agreement can be declared void or it can be continued as it is at the option of

the party whose consent is affected by coercion.

For example,

Dimpy was married to Munna, the consent to which was given due to coercion.

Dimpy can now choose to continue the marriage or declare the marriage as

without consent therefore voidable.

BY

LAWVASTUTAH

REFERENCES:

1. Indian Contract Act, 1872

2.

Pollock & Mulla, The Indian Contract and

Specific Relief Acts, 16th edition.

3.

Avtar Singh, Contract and Specific Relief, 12th

edition.

4.

Halsbury’s Laws of

India Contract, 2e 2015.

5. Chikkam Ammiraju v. Chikkam Seshamma, AIR 1918 Mad 414, (1918) ILR

41 Mad 33, 34 IC 578 (SB).

6. Askari Mirza v. Bibi Jai Kishori, (1912) 16 IC 344.

7. Astley v. Reynolds, (1731) 2 STR 915: 93 ER 939.

8. Muthiah Chetti v. Karuppan Chettiar, (1927) 50 Mad 786, 105 IC 5,

AIR 1927 Mad 852.

Comments

Post a Comment