BAIL JURISPRUDENCE: A PRAXIS OF DISCRETION OR PERQUISITE OF CIRCUMSTANCES

“He does not stay in jail because he is guilty,

He

does not stay in jail because any sentence has been passed,

He

does not stay in jail because he is any more likely to flee before trial,

He stays in jail for one reason - Because he is poor,”

Such

solemn and wise words are of Former US President Lyndon B. Johnson at the time

of signing the Bail Reform Act 1966[1].

The

Cambridge dictionary defines ‘bail’

as,

“an amount of money that a person, who has

been accused of a crime, pays to a law court so that they can be released until

their trial. The payment is a way of making certain that the person will return

to court for trial.”[2]

The term 'bail' has not been defined under the Indian Penal Code, however, its origin

can be recalled to the era of the Roman Empire.[3] The

concept of bail can be traced back to 399 BC, when Plato tried to create a bond

for the release of Socrates. Even in the Salisbury Cathedral’s Magna Carta and

the Statute of Westminster, matured and established procedure for bail can be

observed. It can also be seen in medieval England, where the custom grew out of

the need to free untied prisoners from disease ridden jails while they were

waiting for their delayed trials to be conducted.[4]

By

this definition of bail, very simple meaning of bail was intended, but over

the years this meaning has evolved to become more complicated instead of

getting simpler. The only objective behind introducing this system was to

suffice and espouse the doctrine of “innocent

until proven guilty”.

With

the emergence of English Common Law, the bail system evolved with values of

personal freedom and security of the politico-legal system. As far as the

Indian scenario of bail jurisprudence is concerned, it is governed by the Code

of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (hereinafter referred to as CrPC). The CrPC does

not hold any definition for bail. It only distinguishes between bailable

offence and non-bailable offences. Section 436, Section 437 and Section 439

govern provisions relating to bail in the CrPC.

As

there is no distinct legislation illuminating the ground for bail, it is often

required to rely upon the precedents set by various High Courts and the Supreme

Court. The Supreme Court, over the years, has delivered important judgments

relating to bail in non-bailable offences. These judgments often guide lower

courts while deciding bail applications. Some of them have regarded bail as a

right to an accused, upholding fundamental rights given under Article 22 against

illegal detention and reiterated the dictum, ‘bail no jail’,[5]

[6]while

others limit those fundamental rights so as to protect the interest of the

society, and give incarcerations a punitive aspect.[7]

Various

decisions of the Supreme Court associated with bail jurisprudence have led to a lot of interests, culminating in heated debates. Nevertheless, to understand

the true implications of all these decisions and how they determine the

pre-established notion over bail jurisprudence in India, it is necessary to

explore the doctrine of presumption of

innocence.

The

principle of presumption of innocence represents

far more than a value of evidence. It embodies freedom from arbitrary detention

and serves as a bulwark against punishment before conviction.[8]

In theory, pre-trial detention is permissible only for preventing the accused

from absconding, committing further offences and tampering with evidence or influencing

the witnesses. It is not to be served as a punitive or preventive punishment.

[9]

This article argues about how these parameters have been used inconsistently and

nebulously over the years by the Indian Courts and point out the ramifications

of such decisions on the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. In

addition to these parameters, courts have always relied upon the gravity of the offence, which has

become a decisive factor and a reason for denial for most of the bail

petitions.

In

a nutshell, Bail applications often get considered based on three factors,

I.

Gravity of offence,

II.

Possibility of accused tampering with evidence

and pressurizing witnesses, and

III.

Possibility of accused fleeing from justice

i.e. absconding after bail.

However,

these are not hard and fast conditions to be considered while granting bail

applications but these conditions prevail under the very saying, ‘discretion of the court’ that is

presiding over the matter.

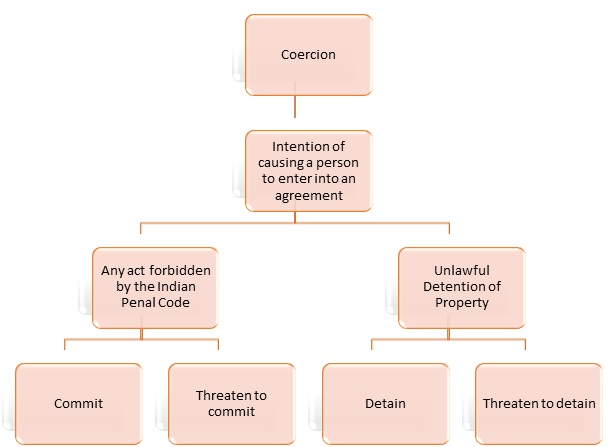

The Gravity of Offence: A Subjective Test

In

Anil Kumar Tulsiyani v state of U.P. and

Anr.[10],

the Supreme Court held that gravity of offence should be the main consideration

while deciding a bail plea of an accused in a non-bailable offence. The instant

case was a challenge to an order of bail granted by the Allahabad High Court.

The High Court granted bail to the accused charged with section 302 read with

201 of the Indian Penal Code, based on the lack of fingerprints on the weapon

used by an accused and no criminal history. It was also argued that there had

been no misuse of liberty during the period as well as no allegations of the prosecution

witnesses being influenced or any apprehension of the accused absconding or

thwarting justice. Though these considerations actually served the purpose the

bail jurisprudence actually intended to, the Supreme Court cancelled the bail

granted by the High Court on the grounds that the High Court did not take cognizance

of the gravity of offence alleged. If the mere purpose of bail is to assure an

accused’s presence at the time of trial, then is it really necessary to dwindle

over the gravity of the offence, which does not have any parameters to measure as

to which offence is severe and which is not.

The

Supreme Court’s next judgment came to contradict its own previous decision. In Prabhakar Tewari v State of U.P. and Anr[11],

the Supreme Court held that the gravity of offence cannot be the ground for

denial of bail. The facts of the cases are as such - An appeal was made against

the Allahabad High Court’s decision of granting bail to an accused charged under

section 302 read with section 34 of IPC. The accused had several cases pending

against him and had been named in the statement forming the basis of the FIR.

The two-judge bench of the Supreme Court favoured the decision given by the

Allahabad High Court and ruled that factors like gravity and seriousness of

offence alleged against an accused by themselves cannot be the basis for

refusal of prayers for bail.

The same ruling can be traced in Sanjay

Chandra v CBI [8] where the Supreme Court set aside an order of

Delhi High Court which rejected a previous appeal made by an applicant by stating

that the “allegations were itself sufficient

to deny bail.” The accused had been alleged of an economic offence which

had incurred a loss of Rs 30,000 crore. But the Supreme Court reversed the High

Court’s order by taking cognizance of the completion of the investigation and prospective delay in the trial, stating that the

right to bail is not to be denied merely because the sentiments of the community are against the accused.

There

appears to be a conflict of opinions in these judgments. This inconsistency often

leads to judicial perplexity as to which one is to be relied upon. All of these

judgments had been given by division benches of the Supreme Court which makes

it more difficult to determine which one has binding nature. Most of these decisions

have been pronounced at the discretion of the judge presiding over the matter.

The Supreme Court in Union of India v

Kuldeep Singh[9] has quoted Lord

Camden’s word,

"The discretion of a judge is said to be

the law of tyrants; it is always unknown; it is different in different men; it

is casual and depends upon constitution, temper, and passion. In the best, it

is oftentimes caprice; in the worst, it is every vice, folly, and passion, to

which human nature is liable.”

The possible remedy

A possible remedy to this situation would be a legislative one. It needs to reconsider the existing bail

provisions that are mostly based on subjective opinions and discretion. The

bail jurisprudence needs to be amended by including objective considerations

such as criminal antecedents and the accused’s status in society. It would subside

the repugnancy in the present provisions.

In, this regard, the American version of Bail Reforms can be considered a knight in

shining armour. The Bail Reforms Act,

1966 [10] made substantial changes in federal pretrial release

and detention practices. The Act obligated to have clear and convincing evidence that the accused had violated

stipulated bail conditions. This obligation made substantial changes in the United

States’ pre-trial detention figures. Though the United States has the highest

incarceration rate in the world, only 20% of its prisoners are under-trial,

contrary to Indian figures which are as high as 67% for under-trial, and 46%

for convictions after-trial. If India really wants to deter crime, the increase

in the conviction rate is necessary and not the proliferation of pre-trial

detentions. It is worth noting that 53% of India’s under-trial population

consists of Muslims, Dalits and Adivasis, 29% are not formally literate and 46%

have not completed secondary education which makes them more vulnerable to

present bail provisions.[12]

Nevertheless,

our system needs to follow the notion of presumption of innocence in a concrete

form, rather than focusing on the verbal aspect. To serve that end, bail

reforms, through legislation have become the need of the hour.

By

Harshal Kshirsagar &

III B.A. LL.B

ILS Law College

[1]Hussainara Khatoon

& Ors v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar, AIR 1979, 1369 ( SC, 1979 )

[2]Definition of Bail,

Cambridge Dictionary, available at https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/bail

[3]Bail Bonds 101, Available at https://app.leg.wa.gov/committeeschedules/Home/Document/168850#:~:text=The%20Romans%20were%20the%20first,was%20not%20bearing%20a%20weapon.

[4]Mohd. Kumail Haider, ‘The Basic Rule of Bail and Safoora Zargar’s

Case: Stretching Law and Facts Thin’, The Leaflet, available at https://www.theleaflet.in/the-basic-rule-of-bail-and-safoora-zargars-case-stretching-law-and-facts-thin/#

[5] Hussainara Khatoon

& Ors v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar, AIR 1979, 1369 ( SC, 1979 )

[6] Dataram Singh v. The

state of Uttar Pradesh, ( SC, 2018 )

[7] Rajesh Ranjan Yadav

and Pappu Yadav v. CBI, ( SC, 2007 )

[8] Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia

v. State of Punjab, AIR, 1980,1632 ( SC, 1980 )

[9] Nagendra Nath

Chakravarti v. King-Emperor, AIR, 1924, Cal 476

[10] Anil Kumar Tulsiyani

v. State of U.P. & Anr, (SC, 2006)

[11] Prabhakar Tewari v.

The State of Uttar Pradesh, (SC, 2020)

[12] Amnesty International,

Justice Under Trial: A study of Pre-

Trial detention in India, available at https://amnesty.org.in/justice-trial-study-pre-trial-detention-india/

Comments

Post a Comment