THE ADULTERY LAW IN INDIA

THE CONSTITUTION OF I, YOU AND WE[1]

“It’s time to say that husband is not the master of his wife[2]. And any provision that treats woman with inequality is unconstitutional.” [3]

These lines were read at the Supreme Court of India on

the historic day of 27th September, 2018 when the 158 year old adultery law was getting decriminalized

under the banner of being unconstitutional and grossly discriminatory.

Image Source: https://bit.ly/36SiIRX

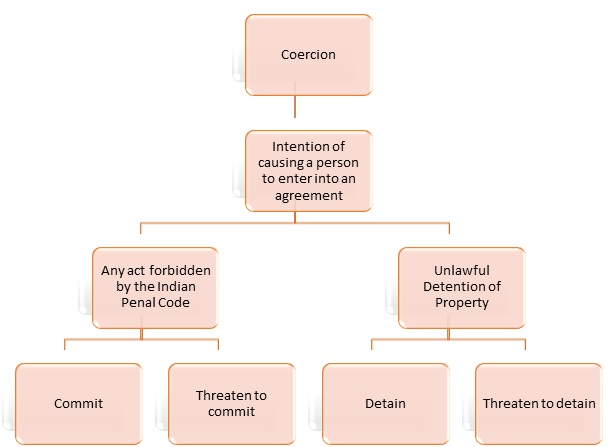

Adultery law had been given under section 497 of the

Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1870 as-

“Whoever has sexual intercourse with a person who

is and whom he knows or has reason to believe to be the wife of another man,

without the consent or connivance of that man, such sexual intercourse not

amounting to the offence of rape, is guilty of the offence of adultery, and

shall be

punished with imprisonment of either description for a

term which may extend to five years, or with fine, or with both. In such case

the wife shall not be punishable as an abettor.”

Facially, the provision appears to be beneficial to a

woman[4], but it is,

in reality, a notion based on invisible paternalism, which stems from the

assumption that women are like chattel or properties to their husbands.

For better understanding, it is essential to read

section 497 of IPC, 1870 with section 198 (2) of the Code of Criminal

Procedure, 1973 which only considers the husband of an adulterous wife as aggrieved party, it reads as-

“No person other than the husband of the woman

shall be deemed to be aggrieved by any offence punishable under section 497 or

section 498 of the said Code: Provided that in the absence of the husband, some

person who had care of the woman on his behalf at the time when such offence

was committed may, with the leave of the Court, make a complaint on his

behalf.”

Section 198 (2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure

confers a right on the husband to prosecute the adulterer; however, it does not confer

upon the wife the right to prosecute the woman with whom her husband has

committed adultery neither does it confer a right to prosecute her husband who

has committed adultery with another woman.

The underlying idea of section 497 is that wives are

properties of their husbands and anyone who infringes that property right shall

be punished in accordance with the statute. But this provision does not recognize

the same right for wives over their husband. So, if her husband commits

adultery, she cannot take any action against him or the other woman

(married/unmarried/divorced/widow). Only the husband of that woman can file a

criminal suit in a court of law. Even then, the wife would not have any say.

The very fact that the offence is cognizable only with the consent of the

husband emphasizes the patriarchal nature of this provision.[5]

Tabular representation might help in this regard:

When the adulterous man is married:

|

Status of adulterous woman |

Adulterous

man (Married) |

Husband of

Adulterous woman (if she is married) |

Wife of an

adulterous man |

Chances of

adulterous men getting prosecuted |

|

Married |

Punishment if proven guilty |

Can file a suit |

Cannot do anything |

High |

|

Unmarried |

No Punishment |

No husband |

Cannot do anything |

None |

|

Divorced |

No Punishment |

No husband |

Cannot do anything |

None |

|

Widow |

No Punishment |

No husband |

Cannot do anything |

None |

When the adulterous woman is married:

|

Status of an adulterous man |

Adulterous

woman (married) |

Husband of

an adulterous woman |

Wife of an

adulterous man |

Chances of

adulterous man getting prosecuted |

|

Married |

Exemption from criminal sanction |

Can file a suit |

Cannot do anything |

High |

|

Unmarried |

Exemption from criminal sanction |

Can file a suit |

Cannot do anything |

High |

|

Divorced |

Exemption from criminal sanction |

Can file a suit |

Cannot do anything |

High |

|

Widower |

Exemption from criminal sanction |

Can file a suit |

Cannot do anything |

High |

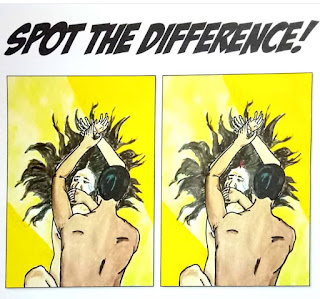

From the above tables, it can be seen that

the wife of a man who has committed adultery would have no access to the whole

legal recourse. The mirror image of this constitutional infirmity[6] is that the

wife of the man who has engaged in such act, cannot claim infringement

of her sexual rights over her husband, simply because there exists no such law

that recognizes her rights over her husband’s sexuality.

But the same is not the situation when it comes to the

husband of an adulterous wife. Whether or not an adulterous man would be guilty

of an offence for sexual intercourse with another man’s wife,

depends exclusively on whether or not the husband of that woman were to consent or

to connive. It means that the adulterous man will have his fortune at the hands

of the husband of the adulterous woman, at whose choice

he will either be prosecuted or extricated.

Law does not make it an offence for a married man to

engage in an act of sexual intercourse with a single woman. In this condition,

the provision does not assume the sanctity of marriage to be defiled. His wife

is not regarded by the law as a person whose dignity and rights are affected,

the protection of which is the sole intent of this provision.

The underlying basis of not penalizing a sexual act by

a married man with a single woman is that she is not the property of a man[7]. Thus, there

is no one to get offended, and no one to get their rights infringed. So there

is no crime at all.

The Court in Sowmithri Vishnu[8] regarded

section 497 as an offence defiling the sanctity of a matrimonial home, where the

husband gets an opportunity to secure his sexual rights if they are infringed

by anyone, but it fails to recognize the wife as an important part of marriage

and her exclusive rights over her husband’s sexuality.

And thus, there appears an inequality.

The history of adultery throws light upon disparate

attitudes towards male and female infidelity and reveals the double standard in

law and morality that has been applied differently to men and women.

English historian Faramez

Dabhoiwala in his book “The origins of sex: A history of the first sexual

Revolution” notes that

the purpose of these laws was to protect the property rights of men, where

these laws consider wife as ‘The Property’.

Certainly, Dabhoiwala has got merit

in his statement.

For example-

In 17 B.C., Emperor Augustus passed a law which

stipulated that a father can kill his daughter and her partner when caught

committing adultery in his or her husband’s house.

Emperor Constantine allowed the husband the right to

kill his wife if she committed adultery.

In the fourth and fifth century Britain, adultery came to

be recognized as a serious wrong that interfered with a husband’s rights over his wife.

None of these ancient, medieval laws conferred any

rights on the wife of an adulterous husband to take any action if her sexual

rights are being infringed as a result of her husband committing adultery.[9]

This position had not changed even until 1707, the

year in which the House of Lords ruled that the killing of a man engaged in an adulterous

act with one’s wife is not a

murder but a manslaughter- as jealousy is the rage of a man and adultery

is the highest invasion of property.[10]

Both the 156th Law

Commission Report and the Malimath Committee advocated for

making the offence gender neutral by inserting “whomsoever has sexual intercourse with the spouse of

another…” Though both

the reports had the potential to give an egalitarian wash to this discriminatory

provision with the view to keep the sanctity of a marriage pure and sanitized,

they went unheard and unacted upon by the legislature.

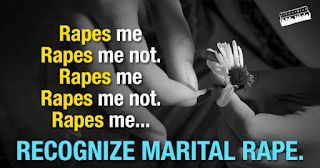

By looking at all of these provisions, it can be said

that the object of adultery laws was not to protect the bodily integrity of

woman, but to allow her husband to exercise control over her sexuality.

A

man’s marital entitlement and his

sexual monopoly over a woman’s purity was the goal to be

achieved with the introduction of this provision. Woman’s purity as

such is an overused, overemphasized and forever talked-about term, but what are

the standards of purity for a man or, the bigger question is if being pure even

a matter of concern for a man in today’s society. For

a woman’s purity, there are often so many

standards, dialects and ideologies but as the common morality suggests, the

paramount quality expected of her is to be loyal to her husband and be obliged

to perform the marital sacred duties which she gets adhered to at the time of

marriage- perhaps at the same marriage where she and her husband both perform

religious ceremonies to mark their assent to reciprocal promises to perform

same duties.

There are so many authorities- the societal one are to

be kept aside to keep a check over the performance of duties of a woman in a

marriage, but the same duty enforcement machinery cannot be seen in case of a

man. He has been given that autonomy to choose and perform his consensual sexual

desires as long as it does not collide with the legitimized sexual interests of

another man. Section 497 punishes an infringer of husband’s rights over

his wife’s sexuality, where it is presumed

that husband is the sole right holder over his wife’s sexuality

and anyone who disturbs it shall be met with criminal sanctions of five years

imprisonment or fine or both. But the wife as such has not been given monopoly

over her husband’s sexuality, as she cannot even

file a criminal suit against another woman who disturbs her rights over her

husband (same rights the husband has over his wife); yet the exclamation is

that there is no such right for a wife and she is not an aggrieved party. Her

husband is not her property and hence she cannot file such a suit. The only

remedy she can have is a divorce.

But an attempt made by the Supreme Court in Joseph Shine can actually

be said to have put an end to woman’s agony. The verdict gave an

egalitarian touch and moulded the law in accordance with the necessities of society. The verdict is itself a celebration of reasoning by

keeping alive the sanctity and mutual entitlement of parties to the marriage.

The Court subscribed to the opinion that the institution of marriage can be

preserved even without putting the sword of the criminal sanctions hanging

right above the head of the spouses, and it realized that adultery is not the

cause of an unhappy marriage- instead, it is the result of an unhappy marriage[11].

Martin Spiegel’s article –“For better or for worse: Adultery, Crime and the Constitution” found a place

to be worth quoted in the Joseph Shine judgement – It is of

experiences, resulting in a variety of choices. For some, adultery is a cruel

betrayal, while for others it is just comeuppance for years of spousal neglect.

In some marriages, sex is the epitome of commitment, while in others, spouses

jointly and joyfully dispense with sexual monogamy[12]

And even if it is not the case, it is the duty of a

constitutional Court to give its citizens the freedom to make bad choices, as

long as it does not collide with the societal interest- the same principle was

enshrined in the US Supreme Court judgment Eisenstadt v. Baird[13].

The judgment does not say whether the act of adultery

is moral or immoral, it does not say if a wife should be given the right to

prosecute her husband, neither does it give its assent to treat woman as

responsible as man in the act of adultery. It simply says, as it is a matter

between three adults, the law should not interfere whether to decide the

morality or legitimacy of the act or tag it as a criminal offence. There are

better ways to signal respect for the institution of marriage and better uses

of law enforcement than policing private and consensual activities[14]. There are

other ways that can be adopted if a spouse is not contended with the adulterous

acts of another, since the Court retains adultery as a valid ground for

divorce.

The Court finally opined that section 497 is a gender

stereotype that the infidelity of men is normal, but that of women is

impermissible. Sexual relations of a man with another man’s wife is therefore

considered as theft of the husband’s property[15]. In

condemning the sexual agency of the woman, only the husband as the aggrieved

party is given the right to initiate prosecution.

This provision marks the footprints of relics of past

and deals with marriage as an exclusive premise for a man to exercise his

sexual choices at his desire and deprives a woman of her voice, agency and

sexual choices as soon as she enters into wedlock.

And at last by naming the adultery law as codified

rule of patriarchy[16], the Court

said that this section is not about protecting the sanctity of the marital

relationship but it is all about protecting the husband’s interest in

his exclusive access to his wife’s sexuality and overruled its

earlier decision in Sowmithri Vishnu and declared section 497 as

unconstitutional.

BY

HARSHAL

KSHIRSAGAR

III B.A. LL.B

ILS LAW

COLLEGE, PUNE

[1] Joseph Shine v. Union of India, WP (Cr) No. 194 of 2017.

[2]. Ibid, at 2.

[3] “Husband is not the master of woman” – Top quotes from Supreme

Court judgement on adultery law, Financial Express, (27/09/2018),

available at

https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/husband-is-not-the-master-of-woman-top-quotes-from-supreme-court-judgement-on-adultery-law/1328730/

[4] Supra 1 at 113.

[5]

Yusuf Abdul Aziz v. State of Bombay, 1954 SCR 930.

[6] Supra 1 at 115.

[7] Supra 1 at 116.

[8] Sowmithri Vishnu v. Union of India, 1985 AIR 1618.

[9] Ibid, at 120.

[10] R v. Mawgridge, 1707 (Kel).

[11] Ibid, at 56.

[12] Supra 10 at 142.

[13] Eisenstadt v. Baird, 1972, U.S. 438.

[14] Ibid, at 143.

[15] Supra 13 at 158.

[16] Supra 13 at 164.

Comments

Post a Comment