TRANSFORMATIVE CONSTITUTIONALISM

Introduction

The Constitution of India is considered a living and organic document. The framers of the Constitution had taken specific precautions to make sure that the law of the land, which gives foundation to the political, administrative, executive and judicial structure of the country, is not rendered a rigid document, incapable of incorporating changes as per the needs of the time. As society progresses and new morals evolve, it becomes the duty of the legislations in place to enable change towards a more egalitarian society. This is where the essence of the concept of transformative constitutionalism lies.

|

| Source- The News Minute |

What is Constitutionalism?

To understand the idea of transformative constitutionalism, it is first essential to look at the meaning of the word ‘constitutionalism’. ‘Constitutionalism’ is derived from the term ‘Constitution’. Constitution of a country seeks to establish and gives foundation to the political organs that constitute the country. The term constitutionalism however is much broader in scope than the term ‘constitution.’ A country with any form of legal structure in place can have a constitution. It is not necessary for it to have a democratic or republic system of governance in place.

Constitutionalism, on the other hand, is a modern political idea, that insists on placing some restrictions on powers given to the administrators or the Government, so that it does not become arbitrary. Constitutionalism is the antithesis of despotism. According to an eminent political scientist, David Fellmen, ‘Constitutionalism proclaims the desirability of the rule of law as opposed to rule by the arbitrary judgment or mere fiat of public officials.’ The idea of constitutionalism is embedded in the establishment of a welfare state.[1] Modern definitions of state are not only focussed on its territorial or sovereign function, it also includes aspect of social, political and economic welfare, as well as upliftment of the masses.

What is Transformative Constitutionalism?

The word ‘transformative’ in itself signifies change. This concept is of fairly new origin and finds its inception in the Constitutional Courts of South Africa. In Professor Karl Klare’s article published in the South African Journal of Human Rights, he described transformative constitutionalism as ‘a long-term project of constitutional enactment, interpretation, and enforcement committed to transforming a country’s political and social institutions and power relationships in a democratic, participatory and egalitarian direction.’[2]

Transformative Constitutionalism in India:

Part III of the Indian Constitution provides fundamental rights guaranteed to all its citizens.[3] It thereby also imposes a duty on the judiciary as custodians of law to protect the rights of all individuals. The Constitution of India provides for equal rights for all, and thus enables transformation of a historically class/caste-based unequal society to a modern egalitarian one. This is in consonance with the opinion of Justice Pius Linga (former Chief Justice of the South African Supreme Court) on removing apartheid and reconstructing a more equal society:

‘This is a magnificent goal for a Constitution: to heal the wounds of the past and guide us to a better future. For me, this is the core idea of transformative constitutionalism: that we must change.’[4]

Transformative Constitutionalism in the Supreme Court Judgements:

The concept of transformative constitutionalism has largely been adopted and deliberated upon by the Supreme Court of India. The application of transformative constitutionalism in the judicial system has been developed in the constitutional courts of South Africa. Transformative Constitutionalism, as an idea has been manifested in numerous High Courts and Supreme Court verdicts in India, expanding the scope of jurisprudence and law. The phrase ‘transformative constitutionalism’ was first time used in an Indian judicial setting in the case of Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India.[5] The verdict given by the Supreme Court on this landmark case, decriminalised section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, to the extent of legalising same sex relationships.

Even before the Navtej Singh Johar case, the concept of transformative constitutionalism was brought forth, without expressly mentioning the term. Time and again, the Supreme Court has elaborated on the transformative nature of our constitution.

· The Supreme Court in State of Kerala and another v. N.M. Thomas and others observed that the Indian Constitution is a great social document, almost revolutionary in its aim of transforming a medieval, hierarchical society into a modern, egalitarian democracy and its provisions can be comprehended only by a spacious, social science approach, not by pedantic, traditional legalism.[6]

· In the NALSA judgement[7], the presiding judges highlighted the function of the judiciary to interpret the Constitution for the welfare of the society, and that in an ever changing dynamic society, sometimes a change in law stimulates social change in the right direction.

· In the Sabrimala Case,[8] the Court had observed that the constitutional provisions including the freedom of religion, must be interpreted in such a way that the dignity of an individual is upheld.

All of these judgements exhibit placing importance on the liberty and dignity of an individual and express the idea of upholding constitutional morality over out-dated ideas of social morality. Apart from the above examples, the Court has specifically endorsed the concept of ‘transformative constitutionalism’ and tried to incorporate this element while pronouncing some of the most progressive judgements.

· The verdict given by the Supreme Court in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India emphasized on the dynamic interpretation of the principles embedded in the Constitution, by acknowledging its transformative and ever-evolving nature. Adopting the idea of transformative constitutionalism, the Court also opined that the ultimate goal of our magnificent Constitution is to make right the upheaval which existed in the Indian society before the adopting of the Constitution.[9]

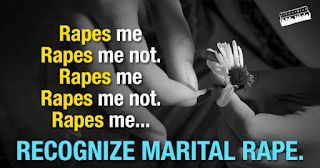

· In Joseph Shine v. Union of India[10], the Apex Court scrapped down section 497 of the Indian Penal Code and thereby decriminalised the act of adultery, which had its foundation in the patriarchal notion that wives are the property of their husbands. The Court in this judgement again applied the concept of transformative constitutionalism. It was held that ‘The hallmark of a truly transformative Constitution is that it promotes and engenders societal change. To consider a free citizen as the property of another is an anathema to the ideal of dignity.’

Conclusion:

Essentially this jurisprudential approach has been applied in cases wherein there has been an element of historical disadvantage and discrimination towards a marginalised section of society. The presence and incorporation of the principle of substantive equality is also closely tied with the idea of transformative constitutionalism. Substantive equality refers to equality of opportunity and therefore equality in the real sense. Another key point echoed in judgements endorsing the application of the concept of transformative constitutionalism is the rejection of past mandates and authority in favour of new ideals that usher in progress and work towards the removal of systematic barriers placed on marginalised sections of society. Finally in the words of Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, ‘Transformation involves a disruption of existing social structures.’, and ‘When you speak of transformative constitutionalism, you speak of infusion of the values of liberty, equality, fraternity and dignity in the social order.’[11]

ILS LAW COLLEGE, PUNE

[1] M.P. Jain, Indian Constitutional Law: Part I, 8 (Lexis Nexis Publications, 7th edn., 2014).

[2] Justice SM Mbenenge, “Transformative Constitutionalism: A Judicial Perspective from the Eastern Cape”,Vol 32, Speculum Juris (2018)

[3] The Constitution of India, Part III

[4] https://www.barandbench.com/columns/are-you-ready-for-the-aftermath-of-the-lockdown last visited: 11th February 2021

[5] Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India, (2018) 10 SCC 1

[6] State of Kerala v. N.M. Johar, AIR 1976 SC 490

[7] National Legal Services Authority v. Union of India, AIR 2014 SC 1863

[8] Indian Young Lawyers Association v. The State of Kerala, 2018 SCC OnLine SC 1690

[9] Supra note 5

[10] Joseph Shine v. Union of India, 2018 SCC OnLine SC 1676

[11] https://www.newsdogapp.com/en/article/5bb9ca3612313a2a9507a78a/?d=false, last visited: 11th February, 2021

Comments

Post a Comment